The New Display Ecosystem — Part I: A few words on HYPE.

July 17th, 2011

It’s been four years since I wrote one of my most popular series of blog posts of all time — “The Ad Exchange Model”. Since then a lot has happened. A whole slew of three letter acronyms has appeared: DSP, SSP, DSP, RTB… Venture capital investments have exploded, we have multiple blogs dedicated to ad-exchanges and it looks like the space has gotten a lot more complicated.

Or put another way… in 2007 I described the world with a simple diagram. Today Terry Kawaja has an industry “LUMAscape” that has logos so small I can’t even read them.

Wow. What the hell happened? We used to have this easy world… publishers sold to advertisers, there was one exchange and then a lot of ad-networks with different pitches. How the hell did we get from there to the above hodge podge “ecosystem” that nobody understands. To help bring some clarity to this world I’d like to kick off a new series… “The RTB Display Ecosystem”. This first post is will primarily be musings on hype… as before we can talk about what’s really happening we all need to step back for a second and realize 90% of what we read is… well… bullshit. I’m sure by now you’ve seen the below diagram. It’s confusing, cluttered and supposed to explain to the world how the new Display ecosystem works. 100s of companies have incorporated this slide in their presentation. I haven’t gone to a single conference where this hasn’t come up multiple times.

How VCs and Bankers brought hype to the industry

Here’s the hard truth people don’t like to hear. The display world is actually not that complicated. Yes the ecosystem has evolved. Exchanges are core tenets of display and there certainly has been a ton of innovation in the data space. But that doesn’t make for 20 boxes on a slide. What really happened is that online advertising captured the attention of silicon valley… complete with a massive influx of VCs, $, TechCrunch posts and of course… HYPE.

You see, Venture Capitalists make money off of home runs. The top companies in a category get great exits, and after that valuations drop off very quickly. To actually be able to justify an investment a VC has to be convinced that the company has a chance at being top in it’s category. Well, this is quite hard to do if the world were simply advertisers, publishers and ad-exchanges. So what do you do? Well… you create a new category, pump millions of dollars in a company marketed as such category, and then hype up this category on TechCrunch as the next greatest thing and rejoice.

Of course VC’s have coffee with each other, hype up their investments to their VC friends (ever heard of an “Echo Chamber”?), and now they’re all clamoring to invest money in other companies who could vie to be a winner in the category and a new slew of companies gets funded.

In 2006 it was impossible to differentiate yourself as an ad-network… and thus every ad-network rebranded as an exchange. In 2007/2008 nobody could raise money as an “ad exchange” that would compete head-to-head with Google and Yahoo. But “SSP” worked out quite well… even though it’s exactly the same business model (queue funding for Rubicon, Admeld & PubMatic, etc.). In 2007/2008 you also couldn’t raise money as an ad-network, but there were plenty of companies interested in helping advertisers spend their money… enter the “DSP” category (queue funding for MediaMath, Turn, Invite Media, etc.). What’s funny is that TMP was doing the SSP business before anybody else and Ad.com has been offering “DSP Services” since .. well, forever!

VCs are also obsessed with investing in “Technology Companies” that build “Scalable Platforms”. You see, Technology is supposed to be sticky. Platforms have ecosystem effects and become $1b companies. To adapt, companies have quickly adjusted their positioning to better reflect attributes that will attract high valuations from said Venture Capitalists. Again, ad-network isn’t sexy, but a technology “Demand Side Platform” is. The funny thing is… it’s hype yet again. Most companies on the LUMAscape slide receive the majority (if not all) of their revenue from media services and not technology fees. Now this line is blurring (more on that later) but what companies are doing is saying they are “technology providers” while behind the scenes they operate exactly like a media company. An “SSP” technology provider hands out tags to publishers and then pays them a check at the end of the month together with a nice excel sheet. This is exactly the same business model of many an ad-network.

Don’t get me wrong — I’m not saying that any of the aforementioned companies aren’t or can’t be great companies. Many of the companies I mention have built terrific technologies and great businesses and some have followed that up with successful exists. But, they did all capitalize on a great marketing opportunity, at the expense of some “old world” companies who were too slow to react.

And this is where VCs and Bankers are actually hurting the industry rather than helping. They are reinforcing the importance of new categories that in themselves shouldn’t necessarily exist. Rather than focusing truly on what a company does they repeat and hence validate what companies say they do.

So what’s next?

Well first, let’s stop the hype cycle and start celebrating real successful businesses for what they have accomplished. Give me more case studies of real results and less BS!

In the coming blog posts I’m going to lay out the new RTB ecosystem and how all the different parties are interacting. Your feedback is as always invaluable so please leave comments with specific topics you’d love covered.

Top 5 Media Startup Mistakes

October 7th, 2010

My first title for this post was “top 5 ad-network mistakes”… then I realized that ad-network was a “bad” term… so intead I’m going to refer to a “media startup”. I’ll put networks, DSPs, trade-desks, dynamic creative providers… any company that buys & sells media (*cough* … looks like a network.. *cough*) under this new “media startup” bucket.

It seems every young media startup I talk to keeps making the same mistakes over and over. Well, here goes in no particular order (even though they are numbered #1-#5) my list of things every startup needs to watch out for… maybe I can help prevent someone from making the same mistake!

#1 – Credit / Payment Terms

A $1M insertion order is amazing.

A $1M insertion order where you get paid net-90 but you pay out net-30 can kill your business.

A $1M insertion order where you get paid net-60 but you pay out net-60… can also kill your business.

Here’s the problem. Agency margins have been on a nose dive downwards for years now. One of the ways agencies drive up their profitability by paying everybody late and making a little extra $ on the interest they earn by keeping the money in their bank account. Even if you think the payment terms line up, just one client that sits on their check for too long can be tdetrimental to your business. If you don’t pay your big sellers they cut you off, killing your network. If you push to hard on the agency, they cut you out of next quarter’s budget.

Proper float & credit management is a must for any network. Have an open conversation with agencies and understand when you can realistically expect to be paid, and then make sure there’s always enough cash in the bank to pay sellers and publishers (and employees!). Many a media startup has gone out of business by badly managing their float.

#2 – Boobs

Did you know that perezhilton.com, wwtdd.com and idontlikeyouinthatway.com are present in some shape or form on every single exchange and supply platform from the aggregators (PubMatic, Rubicon, Admeld, OpenX, etc.) to the big guys (Right Media, Google)? These “Entertainment” sites make liberal usage of pictures of scantily clad celebrities, their sexcapades and lots of other inappropriate content.

Now on a normal remarketing campaign the performance might be great, but there’s nothing worse than an angry email from your advertiser because your ads just showed up next to this page.

In the best case your reputation just took a little hit. In the worst case your advertisers simply refuse to pay out multi-hundred thousand dollar budget amounts…. ouch.

It’s imperative that a network or buying desk has a strategy in place for managing inappropriate and sensitive content. Don’t assume that the “Entertainment” channel is fun sites that you can run any advertiser on… you’ll be in serious trouble if you do. On RTB you obviously get the URL, so use it. Supply platforms also have various forms of brand protection… Advertising online is kind of like teenage sex… first take a sex-ed class to learn what the forms of protection are … and then don’t forget to use protection in practice!

#3 – Malvertisements

Here’s a very common story. One of your sales guys comes in super excited… he just closed an *amazing* deal. $0.75 CPM, no goals, all european countries for a major brand-name advertiser with a huge $100k budget. To top it off, the buyer will pre-pay $50k up front and promises net-15 payment terms.

The deal goes live… and within 24-hours exchanges shut you down and all of your publishers turn off their tags because for some strange reason all of their visitors are complaining that you are trying to install some sort of trojan/malware program with your ads

Yep, there’s bad guys out there that will pay you serious cash to run ads that are really viruses in disguise. When you load them from the office they behave. Enter night-time and they turn into nasty beasts that will cost you publisher relationships, a bad rap with Sandi and potential scrutiny from the feds.

General rule of thumb… if the deal is too good to be true, it probably is. Google has done a terrific job setting up a website to educate the industry about this on www.anti-malvertising.com. Make sure every single one of your sales & ops staff reads this entire site in detail.

#4 – Not Focusing on Sales

If you are building something that’s amazing & scientific, it’s probably the wrong thing to build. No seriously… If you have even one PhD on staff you’re probably doing something wrong.

Quarter after quarter at Right Media I’d work with a team of engineers to push out improvements & features to the optimization system to increase efficiency, ROI & spend. You’d think that in a business running several billion ads a day that this would be the single largest driver of company revenue. Yet… one sales guy at the original Right Media “Remix” Ad-Network single-handedly blew me out of the water one quarter with a single insertion order… and the deal didn’t even use optimization.

Relationships matter… a lot. Not every buyer out there just wants to buy into a magic black box that will auto-magically uber-optimize their life. Advertising is, believe it or not, about more than just clicks & conversions. There’s an inherent understanding of the target audience and the media and buyers want to work with companies that understand how they are thinking and who they are looking for. This means that the buyer wants to talk to someone he can relate to, who listens to him and who he can trust.

This is why every media startup needs a strong sales team. You might have the greatest technology in the world, but if you can’t sell it, it’s not going to get you far. The smart guy in the room? They’re the ones that hire the sales guy that will close the multi-million $ deal. [The above mentioned sales guy went to work for Invite Media, now of course a Google company...]

#5 – Over building technology

To some extent this is a follow-up on the previous point, but so many companies I talk to seriously over-build their technology. The market today is simple. Yes, we will definitely be in a world one day with “traders” sitting at terminals with tickers and fancy secondary future markets and involvement from some of Wall St’s finest…. just not today.

Today, one great trafficker/optimization analyst can beat almost any algorithm out there A team of 5 temps working for a week can apply categorizations to the top 1000 internet sites with similar accuracy to the fanciest semantic engine. A smart BD guy can buy KBB data w/out a deep API integration to a data exchange. A buying strategy of “remarketing” will out-perform any other campaign strategy or behavioral data by at least 10x.

Now don’t get me wrong… there is definitely a market for technology and technology is the only way in which you take the behaviors of brilliant individuals and scale them to be a hundred million $ business. Here’s the problem, most companies start by building technology, then trying to apply it. If you want to be a successful media business you should do the opposite. Hire some great people, watch how they operate, then build technology to automate what they do.

Conclusion…

The above 5 are common mistakes… but there’s one very simple rule of thumb any and every CEO, investor or board member can use to judge the quality of a media startup.

If you ain’t making money, you ain’t doing it right.

Seriously. More than 3 months old with 0 revenue? Likely to fail. Low revenue with high burn? Doomed to fail. The simple answer is it’s easy to get at least one agency to buy in as an early adopter and throw you some $ to “test”. If you can’t do this, you’re doing something wrong!

PS: Shameless self-promotional use of the blog here but… AppNexus is HIRING!!

Price floors, second price auctions and market dynamics

September 25th, 2010

One of the things that is often discussed but not often written about are the market mechanics that surround the new RTB enabled exchanges & SSPs. From a design perspective most marketplaces these days have adopted some modified form of a second-price auction. The winner of the ad impression pays the seller not his actual bid, but the second highest bid.

Second price theory works as follows: Imagine that I’m selling a Monet painting. There are people that want to buy it and each has a maximum price he’s willing to pay but of course doesn’t want to pay a penny more than he has to to get the actual painting. If I tell my buyers that they’ll only pay the second highest price then each can safely give me their maximum price because they know they’ll only pay the amount they need to to beat the next highest guy. That sounds nice right? Second price auctions maximize revenue and make everyone’s life easier and create simple and efficient markets.

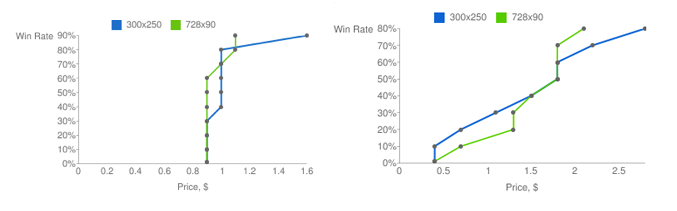

The problem is, reality doesn’t seem to quite follow the theory when we look at advertising today. Take a look at the below yield curves for two publishers coming in from two different exchanges. Both of these exchanges use a second price auction model.

The way the yield curves are read is pretty simple. On the X-axis you have a CPM bid-price and on the Y-axis you have the % winrate — the probability that you will win an impression from this publisher for this ad-size if you bid this price. On the right we see a relatively logical and predictable curve — you can’t win much below $0.40, at $0.50 you win about 10% of the time and above $2.00 you will win about 70% of the time. The higher the price point, the less demand and hence the higher the winrate.

On the left you see a rather curious pattern, below $0.90 one wins nothing whereas at $1.00 you get 80-90% of all impressions. Obviously not an efficient market. In this case, the publisher has set a price floor of about $0.90 for the inventory.

This is pretty common these days in RTB — publishers are absolutely terrified about cannibalizing their rate card and are hence forcing a “premium” for RTB buyers. This is a particularly interesting case because if you look at the actual win-rates it’s pretty obvious that there is barely any demand above their actual floor… or in other words, it just ain’t worth that much. So why would a publisher set a floor and sacrifice their revenues?

What the publishers are afraid of

Fundamentally publishers are afraid that advertisers will “game” their auctions and the net result will be lower effective CPMs.

Let’s take a completely theoretical auction on Google AdExchange for a 29 year old male user seeing his third ad on a specific page about ford pickup trucks on CNN.com who has been identified as an in market cell phone shopper. Four buyers are interested in this specific impression…

- Ford buying the keywords “pickup trucks” — values the impression at a $5.00 eCPM (derived from a CPC price)

- AT&T targeting in market cell phone buyers using third party data at a $3.00 CPM

- A branded Kraft campaign that is trying to reach 29 year old males at a $2.00 CPM

In second price theory each would submit this price, Ford would win the impression with it’s $5.00 bid and pay $3.00 to match AT&T’s second price.

Here’s the problem… frequency & an abundance of supply. Users see multiple ads. Frequency is also by far the most significant variable for optimizing response to ads. Hence each buyer is only interested in hitting this user a limited number of times with their ads.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume that our 29 year old Male, Joe, is browsing a number of different articles on CNN.com and there are 10 different opportunities to deliver an ad to him. Let’s also assume that our buyers continue to bid on each and every impression. To model frequency let’s assume that after each impression delivered the advertiser will bid half as much for each subsequent impression. Under these assumptions here’s how the bids would pan out over a number of auctions:

| Auction | Ford | AT&T | Kraft | Price paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 5.00 | 3.00 | $2.00 | $3.00 |

| #2 | $2.50 | $3.00 | $2.00 | $2.50 |

| #3 | $2.50 | $1.25 | $2.00 | $2.00 |

| #4 | $1.25 | $1.25 | $2.00 | $1.25 |

| #5 | $1.25 | $1.25 | $1.00 | $1.25 |

| #6 | $0.63 | $1.25 | $1.00 | $1.00 |

| #7 | $0.63 | $0.63 | $1.00 | $0.63 |

| #8 | $0.63 | $0.63 | $0.50 | $0.63 |

| #9 | $0.31 | $0.63 | $0.50 | $0.50 |

| #10 | $0.31 | $0.31 | $0.50 | $0.31 |

What we see is that for each auction the publisher’s revenue is maximized with CPMs starting at $2.50 but then very quickly dropping down to $0.63 cents.

Now here’s where theory and practice start to separate. In the above scenario, Ford pays an average of $1.72 CPM to show this user four ads. This is quite a bit higher than the average CPM and Ford decides to try a new bidding strategy to try to reduce his cost. Rather than always putting out his maximum value to the ad exchange he holds back a little bit and decides not to bid until the 6th impression.

Here’s what happens:

| Auction | Ford | AT&T | Kraft | Price Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | no bid | $3.00 | $2.00 | $2.00 |

| #2 | no bid | $1.50 | $2.00 | $1.50 |

| #3 | no bid | $1.25 | $1.00 | $1.00 |

| #4 | no bid | $0.63 | $0.50 | $0.63 |

| #5 | no bid | $0.33 | $0.50 | $0.33 |

| #6 | $3.00 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #7 | $1.50 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #8 | $0.75 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #9 | $0.38 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.33 |

| #10 | $0.19 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $0.25 |

What you see in the above is that Ford now buys four impressions, slightly further down in the users session but for an average CPM of $0.33… 81% cheaper than were he just to submit a bid on each and every impression.

Of course this is a hypothetical situation, but it does show a point — if demand is limited then for buyers a very simple bidding strategy can have a large impact on cost and greatly increase ROI.

Let’s now imagine that the publisher realizes the advertisers are doing this and sets an artificially high floor price to try to protect his margins — $1.50. Instead of accepting a paying ad he will show a simple house ad instead.

Here’s now what the auction looks like:

| Auction | Ford | AT&T | Kraft | Price Paid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | no bid | $3.00 | $2.00 | $2.00 |

| #2 | no bid | $1.50 | $2.00 | $1.50 |

| #3 | no bid | $1.25 | $1.00 | psa |

| #4 | no bid | $0.63 | $0.50 | psa |

| #5 | no bid | $0.33 | $0.50 | psa |

| #6 | $3.00 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $1.50 |

| #7 | $1.50 | $0.33 | $0.25 | $1.50 |

| #8 | $0.75 | $0.33 | $0.25 | psa |

| #9 | $0.38 | $0.33 | $0.25 | psa |

| #10 | $0.19 | $0.33 | $0.25 | psa |

The publisher has certainly succeeded in driving up the average Ford CPM — back up to $1.50 from the earlier $0.33. CPMs are down to $0.65 but the overall average is actually *down* from $0.71 CPM.

Here we see how the artificially high price actually ends up driving overall revenue down by limiting the number of impressions sold significantly.

Of course those of you paying attention would point out that a lower floor could potentially increase revenue over the no floor situation!

So what gives?

Direct marketers have known the above for years. This is why very few pure response driven buyers pay rate-card for the ESPN home page. What scares publishers is the idea that branded buyers could start doing the same thing. The knee-jerk reaction in this case is to set arbitrarily high floor prices on marketplace inventory to try to protect the channel conflict.

Floor prices themselves aren’t necessarily that bad. In fact, there are good reasons for setting them. First, there are brand buyers that are paying rate card for guaranteed inventory — there is no reason to expose that same inventory to those buyers on a marketplace for a much lower rate. In other cases, a publisher might just be better off displaying internal house ads rather than showing a crappy blinky offer that annoys visitors at a low CPM.

For example, imagine you’re ESPN and you have a new “Videos” section where you just started running pre-roll ads $30 CPM. If ESPN were to show the crappy blinky offer (not that they have the demand problem), they’d make $0.10 for a thousand impressions and probably risk losing a small percentage of their audience in the process. On the other hand, a benign house ad announcing the new “Videos” section of the site would both increase site-traffic and visitor loyalty, but actually generate revenue. If they get 5 clicks per thousand impressions on the house ads they’ll actually be able to net out $0.15 in advertising revenue from the 5 pre-roll impressions served on the video site (and even more if users watch more than one video).

Going back to market mechanics

Let’s go back to Market mechanics for a second. Today what we need to avoid are knee-jerk set crazy high floor prices — a floor price that is too high will simply result in lower RPMs for the publisher. Publishers must understand that there is a significant pool of demand, specifically the ROI & response driven side, that simply won’t buy the inventory for rate-card prices.

In the end it comes down to information and controls. Publishers need to understand the market mechanics and the yield that they can derive from their inventory. At the moment I’m not aware of any major marketplace providers that supply this type of information.

I have a lot of thoughts on the tools and controls a pub should have and also on how one might change market mechanics away from a true 2nd price auction to efficiently deal with this — but I think this post is getting long enough… I’ll save that for the next one (which hopefully won’t be 5 months in the making!)

I don’t care who you say you are, what do you DO?

May 3rd, 2009

One of the things that boggles my mind is how massively fragmented and confusing the display world still is. It’s been over three years since the first ad-exchange launched yet the world hasn’t significantly changed. What makes matters more confusing is that there is no consistent terminology to describe what a company does. It seems everybody describes themselves as either a platform, marketplace or exchange — so what’s the difference?

A company can call itself a publisher, an agency, a network, a broker, a marketplace, an exchange, an optimizer — what does it all mean? What’s the difference between Right Media and Contextweb? Admeld and Rubicon? That’s really the problem — today’s commonly used labels are useless.

Instead of evaluating a company based on labels, evaluate it based on the services it provides, technology it has, the partners it works with, the revenue model and the media revenue it facilitates. Note — below I focus entirely on companies that in some shape or form touch an *impression* — either as a technology provider, buyer or seller. There are peripheral companies that provide a whole world of supporting services, but I’m leaving those out for now to avoid confusion.

Services

Each company provides certain core services to partners, customers and vendors. These primarily center around the relationship the company has with the media that flows through it.

| Service | Description | Example | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selling of Owned & Operated Media | The company represents and sells media inventory that it owns. | Yahoo selling inventory on Yahoo Mail. New York Times selling it’s inventory |

Company’s sole objective is to maximize CPMs and revenue. |

| Arbitrage of Off-Network Media | The company resells media inventory that it acquires from other services. | Yahoo selling users on the newspaper consortium. Rubicon selling inventory from it’s network of publishers. |

Company takes arbitrage of the inventory which means that it’s incentivized to buy low and sell high to maximize it’s own revenue rather than that of the inventory owner or the advertiser. |

| Inventory or Advertiser Representation Services | The company helps inventory owners sell inventory at a fixed margin. | AdMeld serving as a direct rep for publishers remant X+1 managing all campaigns for a specific advertiser or agency |

Company is incentivized to maximize revenue for the inventory owner or ROI for the advertiser. |

| Data Aggregation | Company aggregates user data and resells it | BlueKai’s data exchange Exelate’s data marketplace |

Company hates Safari and IE8 |

Technologies

There are certain core technologies that define what a company does. Note that you will find technologies such as dynamic creative optimization, behavioral classification and contextualization missing from the below list as they are differentiators — they don’t define what a company does but provide a competitive advantage over the competition.

| Technology | Description | Example | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internally available adserver | Company has a proprietary in-house adserving system. | Specific Media has it’s own proprietary adserving technology that it uses to manage it’s network. | Company sees technology as a competitive asset against competitors. |

| Externally available adserver | An adserver that the company licenses (either free or paid) to third party companies to manage their own online media. | OpenX providing their hosted adserver to publishers Invite Media’s cross-exchange Bid Manager platform Google’s Ad Manager |

Multiple companies using the same platform provides both aggregation and consolidation opportunities. Technology in this case helps build an open platform (since everyone has access). |

| Internal Trading | Inventory run through the externally available adserver can be bought and sold internally | Google’s AdEx allows multiple participants to use the externally available adserver to buy and sell media. Right Media’s NMX customers can buy and sell media to each-other directly. |

There is a network effect related to the size of the platform. The more participants the more value there is for everybody involved. |

| Buying APIs | Company provides an API, either real-time or non, through which buyers can upload creatives and manage campaigns. | Right Media allows it’s customers to traffic line items and creatives using it’s APIs. | Company is empowering buyers to be smarter by enabling deeper integration across platforms. The stronger the APIs, the more the buyers can spend. |

| Selling API | Company provides a real-time API through which sellers can ask in real-time how much company is willing to pay for an impression. | Right Media and Advertising.com respond in real-time to a ‘get-price’ request from Fox Interactive Media’s auction technology | Company can value inventory in real-time. |

Size Matters

Last but not least, the size and the partnerships of a company matters. I’ve written before about the perils of building technology in a void. You can have the most amazing platform that provides great services, but if you’re only running a few thousand dollars a month it’s all moot in the grand scheme of things.

Size can be measured either in impressions or revenue, the latter being far more telling. Getting a billion impressions of traffic a day isn’t hard these days — between Facebook and Myspace alone you probably have close to fifteen billion impressions of traffic running daily.

There’s a huge difference between a partnership and a media relationship. If you’re willing to foot the minimum monthly bill, anybody can buy Yahoo’s inventory through the Right Media platform. That doesn’t say much about who you are as a company. A partnership is different — it might be deep API integrations tying two platforms together or co-selling and marketing a joint solution.

What does it all mean?

Phew… that was a long list, so what does it all mean? Well, the above provides a slightly less fuzzy framework than the classical “ad-network”, “marketplace” or “exchange” commonly used labels to describe a company. Let’s look at a few examples:

Rubicon Project provides publisher representation services through it’s network optimization platform, arbitrages inventory through it’s internal sales team has both an internal and has an externally available adserver (one for the sales team and one for publishers) and is rumored to be working on real time buying APIs. That’s a hell of a lot more descriptive than “publisher aggregator” or “network optimizer”. The one thing I always find confusing about rubicon is that it their incentives seem to be fundamentally misaligned. How can you both arbitrage inventory and serve as a publisher representative? Updated (5/3/09 @ 8pm EST) — I seem to be misinformed. Per comments, Rubicon does not sell inventory directly to agencies.

Compare this to AdMeld which provides publisher representation services through it’s network optimization platform — an externally available adserver — and provides buying APIs (currently via passback). So what’s the difference with Rubicon? Well, one has an internal ad-network and the other doesn’t — different incentives. Publishers are starting to treat Rubicon as another ad-network in the daisy chain whereas AdMeld sells all remnant inventory as a trusted partner.

ContextWeb has an internal adserver (with a self-service interface… I don’t count that as external), they arbitrage inventory, and provide buying APIs. Compare this to Right Media which has an externally available adserver, buying and selling APIs, internal trading, data aggregation and arbitrages media (through BlueLithium/Yahoo Network). Both are “exchanges”, but clearly there is a pretty big difference between the two!

Of course if you get to Google your mind starts to explode just a little bit — as they do everything. Seriously. They buy & sell, have multiple adservers, provide buying APIs, internal trading, data aggregation…

Final Thoughts

I hope this post has given you some ways to start thinking about companies in the online ad space. I’d love to hear your feedback in the comments — what core services & technologies am I missing?

Now — next time someone says — “I’m an exchange”, why not ask — “Ok, that’s great, but what do you really do.”

Advertise less, make more money!

December 15th, 2008

Yahoo Research via Geeking with Greg:

In Web advertising it is acceptable, and occasionally even desirable, not to show any [ads] if no “good” [ads] are available. If no ads are relevant to the user’s interests, then showing irrelevant ads should be avoided since they impair the user experience [and] … may drive users away or “train” them to ignore ads.

What a crazy idea — what if one were to actually make more money by not advertising. It makes total sense. We’re inundated with media. Our eyes have been trained to ignore those lovely 160×600 and 300×250 size objects that we see all over our web pages — especially on social networking sites where our users spend so much time.

This fascinating paper on negative externalities further reinforces this idea:

Most models for online advertising assume that an advertiser’s value from winning an ad auction [...] is independent of other advertisements served alongside it in the same session. This ignores an important externality effect: as the advertising audience has a limited attention span, a high-quality ad on a page can detract attention from other ads on the same page.

I’m sure everyone by now is familiar with Pareto’s law — otherwise known as the 80/20 rule. Applied to advertising Pareto’s law states that 20% of impressions generate 80% of the revenue — and yes this is true for most web 2.0 properties that I have worked with. So what if we stopped showing ads on the 80% that were only generating 20% of the revenue?

Instead of showing crappy CPA offers the publisher should show either nothing at all, or some relevant site content. Show a snippet of the friend-feed, or maybe a list of ‘online friends’. Show “interesting related links”, or “new photos posted”… it doesn’t really matter. Show something that is of interest to the user. The point of the exercise is to train the user to start looking at this specific space again.

In the short term this may very well sacrifice 20% of revenue, as users who were previously inundated with ads are learning to trust those slots again. Longer term we get more user engagement which means higher rates on the other 80% of revenue. I wouldn’t be surprised if you saw a 50% increase in engagement just by showing 80% fewer ads — and that increase in engagement translates directly to higher rates and a fatter bottom line.

There are a world of other benefits too. First of all — fewer ads means happier users. It also means fewer creative issues (whether content or malvertising). The publisher can also use this as an opportunity to drive traffic from lower to higher monetized sections of the site. Eg, Myspace could drive users from the low $0.15 CPM User-Generated Content pages over to the very brandable ‘Movies’ section. And last but not least — showing fewer ads will create a sense of scarcity around what today is most certainly considered “bulk” inventory. This scarcity will help justify higher rates on the premium guaranteed buys — further helping to fatten up that bottom line.

If this is obviously so good, why is nobody doing it? Well there’s only one small insignificant problem… Publishers have no way of identifying the top 20% of impressions. You see, especially on social networking sites a huge portion of that 20% are impressions that are sold behaviorally via ad-networks and exchanges. Those ad-networks and exchanges need to see the full 100% to be able to cherry-pick the 10% that are valuable to them thereby making it quite difficult for the publisher to “not show ads” on worthless impressions. In fact, since all reporting is aggregated, most publishers don’t even realize that the majority of their revenue comes from a relatively small # of impressions.

How do we get around this? Well… that’s another blog post =).

Introducing “buy side” versus “sell side”

December 10th, 2008

In my last post I said that the traditional ad network model was dying — what I didn’t talk about is how I think the network model will evolve over the coming years.

The fundamental flaw with the traditional network model is that the network is incentivized to optimize it’s own revenue — not maximize value for the advertiser. As long as you keep the advertiser happy that he’s getting a great ROI, and the publisher gets his paycheck — the network can keep the rest. The less demanding the advertiser, the less intelligent the advertiser — the better for the network!

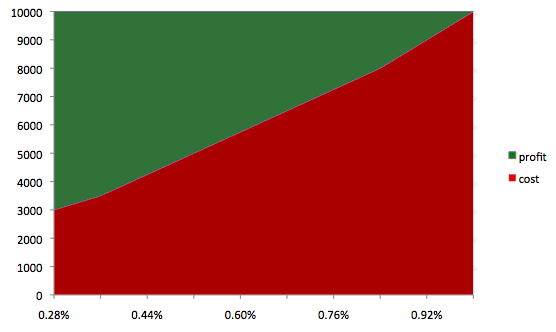

Let’s take a simple example — A classic agency IO line item has a size, cpm, budget and some basic targeting parameters and goals. For example, one agency may buy $10,000 worth of US based inventory at a $0.50 CPM for 728x90s with a target CTR of 0.5%. Another way to think about this is that $10,000 @ $0.50 is 20M impressions, and at a 0.5% CTR means the agency is expecting to receive 100,000 clicks.

Now the smart network will go out and see how cheap he can go and acquire 100k clicks on news inventory. Why? Well, assuming he can deliver the volume his revenue has already been fixed — it’s $10,000 no matter what he does. The only thing on the line is whether or not this IO will be renewed or expanded next quarter. Since cost is the only variable the network can manipulate to increase profit he will go out and find the cheapest possible inventory that at least a 0.5% click through rate. The chart below demonstrates this with fictitious data. Buying cheaper inventory results in a lower CTR, but also significantly higher profits. All the network has to do is figure out how happy he wants to make the advertiser — just happy enough to renew (and maybe increase) next quarter’s IO, but not quite enough to cut into his healthy profit margin.

Network Profit & Cost w/ Campaign Performance

Now you might think that this only works if advertisers are buying on a CPM, but sadly that is not the case. Whether it’s on a CPC, or even a CPA — it’s all about finding the cheapest way to fill the requirements. You see, there is actually a strong difference in lead-value depending on the source of the inventory. A click from Yahoo’s homepage is actually worth significantly more than a click from a social networking site such as Myspace or Facebook. Similarly, a lead or conversion from the New York Times (one of the most affluent properties on the web) is worth more than a conversion from helpforhomeowners.org. The majority of buyers out there today do not have the necessary lead tracking tools to accurately identify who is sending them good or bad leads.

I think that it’s this fact alone that justifies the need for central exchanges — which charge transparent fees to connect buyers and sellers. The problem with exchanges is that most agencies lack the deep buying knowledge that the ad-networks have. Just because there direct access to billions of impressions per day doesn’t mean that anybody *can* just buy them effectively. It takes serious skill and agencies still need help finding the inventory that will work best for their campaigns.

It is here that we are starting to see a new breed of ‘network’ — 100% advertiser focused buying networks that put their interest squarely with the actual agency. By charging transparent fees (say 10-20%) and being open about the inventory they buy — the agency can trust that efforts are spent optimizing and acquiring the best possible inventory for each campaign — not the cheapest that will fulfill the actual requirements.

Yet there is also a longevity question. Although agencies lack the skills to buy effectively today, this is something that they are all working on — at what point does the agency become a competitor of the “buy side” network — and visa versa? Logically these business don’t need to be separate, but practically I wouldn’t be surprised if they remain that way. Agencies are naturally filled with “right brain” people — they are creative, imaginative. Networks are naturally “left brain” focused — analytical.

Next post — we’ll take a look at the publisher rep firms and their growing role over the coming years.

The World is a’ Changing

November 10th, 2008

Unless you’ve been living under a rock somewhere you’ve probably heard that the whole world is crumbling around us. We’re entering the great depression, guard your cash, no more VC, we’re all POOR.

Well, first let me reassure you — so far the nuclear winter hasn’t started yet. The data that exists so far has been fairly sparse and inconclusive — Google is up, AOL is down… Rubicon claims the sky isn’t falling whereas PubMatic claims prices are steadily falling. I’ve had quite a few in depth discussions over the past few weeks on exactly this topic — where is the industry headed? How is the economic downturn affecting online advertising? What are the big boys doing? What’s new exciting?

Last week’s AdECN announcement and a short stroll through the booths at AdTech finally motivated me to get up and write another blog post! (sorry for my absence, life is pretty hectic these days). So here goes in no particular order my views of exciting things in the market today and what’s coming next.

The traditional “marketplace” network model is dead

By traditional networks I mean the models that ValueClick, Casale and Ad.com were founded on — networks that were primarily built by matching large amounts of supply and demand. The name of the game was to get as many advertisers and publishers together as possible to build the largest marketplace. Once the network was large enough, ad dollars naturally flowed to these players as they were a “one stop shop” for thousands of publishers. Large margins are made by buying low and selling inventory to advertisers at a higher price.

This model was used by many companies to build incredibly successful networks — and in fact — most of these networks are *still* very successful. The problem is, the world is changing. Namely:

First, access to inventory is no longer a competitive advantage. Between Exchanges, publisher aggregators and a mass influx of social networking inventory — everybody has access to billions of impressions.

Second, agencies want to cut out the middle man. Agencies have started to realize that networks are taking massive cuts out of their media buys while in many cases simply serving as an aggregator. And indeed, with supply easier and easier to get access to, many agencies are launching initiatives to cut out the middle man. Whether it’s the new Havas Artemis system, the Publicis Vivaki network or the WPP 24/7 acquisition — they’re all moving in the same direction.

Essentially — networks are getting pressure from both sides. On the supply side they are getting commoditized by aggregators and network optimizers and on the demand side a new crop of technology companies is attempting to empower agencies to buy directly — cutting off the ‘marketplace’ networks.

The rise of the pubgregatimizer

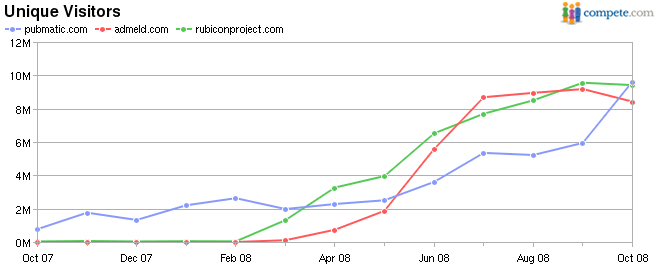

Publishers have finally realized that they might not be the best ones to sell their non-guaranteed inventory. Three well funded companies have emerged that are looking to help publishers navigate the sea of ad-networks and best monetize — PubMatic, Rubicon and AdMeld. I think the value prop is obvious — only the largest of publishers can afford the staff to fully manage the distribution of remnant inventory across various networks. At the moment it looks like the three are neck & neck in terms of unique visitors:

Decreased growth rate will force more accountability for agencies

Although the sky isn’t falling, money is getting scarcer. This scarcity will force everyone along the entire value-chain to be more competitive. This will start with the agencies and go all the way to the publisher — everyone will have to prove both effectiveness and figure out new ways to differentiate themselves from others. Scarcity of dollars will also put pressure on agency margins forcing them to look elsewhere on ways to increase their revenues.

Some initiatives have already started here — Publicis has launched Vivaki, WPP bought 24/7 and Havas has Artemis. Although the exact strategies are vague, one thing is clear — Agencies are going to start getting more involved in the buying process as they see their margins drop to 10% or below whereas our traditional networks (dying per the above) are still pulling in 30-50% margins on their media.

The challenge here is that most agencies aren’t setup to buy effectively online. Buying online is much more about technology, analytics & strategy than it is about creativity, ingenuity and imagination. To buy effectively online an agency needs to start working on it’s brain — which of course is currently largely dominated by “right brain” creative folks and lacking in “left brain” analytics. One of the things we see here as an increase in popularity of the ‘media trading experts’ — networks that focus exclusively on helping agencies buy the best possible media for their clients. Leveraging exchanges & aggregators instead of traditional ties to publishers these networks can serve as an unbiased agent of the agency.

Exchanges will move to real-time integration

Even though only one has made it public — AOL, Yahoo, Microsoft & Google are all working on real-time integrations. Why? Any central trading platform for media needs to support different engines & algorithms. If nobody can differentiate themselves on a platform, then nobody will want to use said platform! Although Right Media was a terrific step forward as the first central trading platform, it’s major flaw is that it took the technology out of the network. Real time bidding platforms solve that by allowing smart advertisers & networks to run their own engines. With the big 4 all working on something… it’s going to be interesting to watch what happens!

This combined with all of the above show a great picture for technology focused ad networks. As I wrote about earlier here and here — it is the difficulty of integration that has limited many an online ad technology startup from succeeding. With supply becoming more and more available in more and more programmatic manners — a time is coming when the guy with the best algorithm will actually stand a chance competing against the guy with the best relationships at WPP.

Final Thoughts

This is an incredibly exciting time in the industry — the whole industry is fragmented, there is little standardization and there is a massive amount of pain. I think big changes are coming. I’ll try my best to be a little more prompt about blogging about it while it happens

Also — if anybody is going to be at Adrevenue 08 and wants to meet up, shoot me a note.

Redirects and Integration, Part II: Hacking Around the Browser

April 17th, 2008

In my last post I talked about redirects and the limitations they posed for online advertising. In this post I’m going to discuss the various workarounds that people have put in place to address the problem. I’m primarily going to focus on serving speed & the “one-way” challenges of redirects as there isn’t much that can be done to address the fact that redirects are inherently insecure.

Fundamentally when you are talking about “integrating” two different serving systems there are two key driving factors: tracking information and influencing the decision. In most cases tracking information is for either transparency or behavioral information. Influencing the decision is also often related to behavior as it’s close to impossible to transplant data from one cookie domain to another. So let’s look at three little ‘hacks’ that people do to make systems play nice.

Replacing a redirect with a tracking pixels

One of the primary reasons why agencies operate their own adservers is to be able to track the # of impressions that their publishing partners are serving. Yet a much simpler method of counting ads that doesn’t involve an entire redirect is to place an “impression tracking pixel” that the publisher (or network) shows on every ad call.

Let’s compare how an impression-tracking pixel impacts the serving speed compared to a more traditional redirect If both a publisher and an advertiser are using a serving system and are using standard redirects (or ad tags) to integrate, each ad call will result in three consecutive requests:

Call 1, Publisher’s Adserver. The first call obviously goes over to the publisher’s serving system. When the publisher’s adserver chooses an adserver he returns to the page either a 302 redirect or some javascript from the advertiser’s serving system. Effectively redirecting the user.

Call 2, Advertiser’s Adserver. In this call the advertiser receives the request, logs an impression and then spits back some HTML (or javascript) that tells the browser to download the ad, generally from a content delivery network (CDN).

Call 3, Creative Content. In the third call the browser requests the actual GIF/JPG/SWF file from a content delivery network and displays the ad.

If each call takes 250ms the total time to serve this ad will be 750ms as no call can occur until the prior one has fully completed. The browser doesn’t know where which advertiser adserver to request content from until he has fully received the publisher’s redirect and then the actual SWF file can’t be downloaded until the advertiser’s adserver has responded with the appropriate HTML.

When an advertiser passes the actual creative over to the publisher and includes an impression tracking pixel the ad-call sequence changes a bit.

Call 1, Publisher’s Adserver. The first call is still to the publisher’s serving system, except rather than returning the actual ad-tag (or redirect) to the advertiser the publisher’s system returns two things. One a call to the actual creative (SWF/GIF/JPG) hosted on his CDN and then a second pixel call to the advertiser’s impression tracking pixel.

Calls 2&3, Creative & Tracking Pixel. Because the user’s browser received both instructions it can now proceed to download both the creative and the tracking pixel in parallel.

If each call takes 250ms then the total time to serve this ad will be 500ms, 250 for the first publisher call and then another 250 for the creative & tracking pixel in parallel.

Benefits: The biggest benefit of the impression tracking pixel approach is that it decreases the time to serve an individual ad — something that will reduce discrepancies and increase the quality of the end user’s experience.

Drawbacks: Of course there are drawbacks with this approach. Trafficking both a creative and it’s associated impression tracking pixel is more work than a simple ad-tag. It also requires more coordination between the advertiser and the publisher

“Forking” an ad-call with an impression pixel

Impression pixels do not have to solely exist instead of a redirect. In fact, they can also be used to supplement existing ad-calls and let third parties “listen in” on an impression stream without giving them the power to manipulate an ad. For example, let’s say that a network uses the Right Media ‘NMX’ platform for their network adserving but is unhappy with the amount of information that he receives from the reporting systems. Said network’s advertisers demand more information from their media-buys — what can he do?

Obviously one answer is to add a redirect to every ad call — this quickly becomes complicated though as the network will have to host the actual gif & flash files, somewhat defeating the purpose of using a 3rd party network adserver. Also, many publishers won’t accept third party served ads from unknown adservers, posing an additional challenge when trying to buy tier-1 inventory.

Another way to address the issue is to insert a tracking pixel into every creative. On every ad-call the network fires off a pixel to his own tracking server which contains the key information that he is interested in — say — creative ID, publisher ID and referring URL. He can then log this information and provide the advertiser with the detailed reports showing exactly where his ads appeared without having to reinvent an adserver!

Using AJAX to load 3rd party content

AJAX has gained a lot of popularity recently. One way that people can integrate two serving systems is by inserting a small bit of javascript that loads the 3rd party content required to either track information or make a decision directly into the browser. For example, let’s say a network wants to know whether a behavioral data provider has valuable data on a user. If the behavioral partner he receives the impression and if not the publisher sends the impression over to one of his regular networks. He could insert a small bit of javascript that sends a request browser-side and loads the behavioral advertiser’s cookie data from the third party domain.

There are some benefits to this approach — timeouts could be set on the actual request limiting the potential slow-down. Also, since the third party isn’t in the redirect stream he doesn’t get full control over the entire impression. The downside is that the decision is made on the client side. This introduces a whole new set of challenges around tracking & writing cross-browser compatible JS.

All these methods are hacks

You’ve probably realized by now that most of the workarounds involve tricking the browser to load some content from different serving systems. Some schemes that I’ve seen get incredibly complex. I remember a customer who wanted to use Right Media’s serving system as the source of inventory but then inject behavioral information from his own cookie domain. The end result was that impressions came into the RM adserver, were redirected to his adserver and then were immediately redirected back to the RM serving system. That’s three ad-calls before an advertiser had even been selected!

That’s about it for now … Stay tuned for part III….

Maximizing network revenue

September 13th, 2007

Many publishers either don’t have a strategy for maximizing network revenue or use aging technies such as daisy-chaining to

Out of all the publishers that I’ve talked to many don’t have a solid strategy for maximizing revenue from ad-networks. Many simply don’t understand how networks price, since most are black-boxes that don’t publish how they optimize and choose which ads to display. Yet, there are a couple factors that I find can be large drivers of revenue.

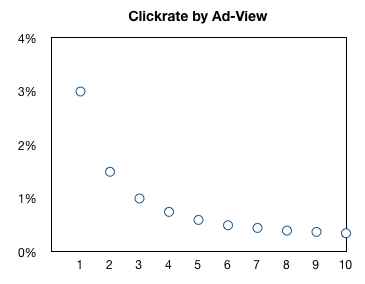

The more times an individual user sees an ad, the less likely he is to respond to it. Ok, seems obvious right? What you may not realize is exactly how quickly user response to an individual ad drops. The following graph is fictitious but representative of the normal response curve of a user on a single site to repeatedly seeing the same ad.

What the above shows is that if you are to maximize revenue you need to start thinking about users and not impressions. A user that’s been on your site for hours and has seen a hundred ads is far less valuable than someone who just logged-on.

Of course every ad-network will tell you that they have a large # of advertisers and deals and that you shouldn’t worry about such things — but lets not forget the Pareto Principle, also known as the 80/20 rule. A small percentage of top advertisers will generate the majority of revenue (and hence higher rates). What that means is that each ad-network will only have one or a couple high CPM ads.

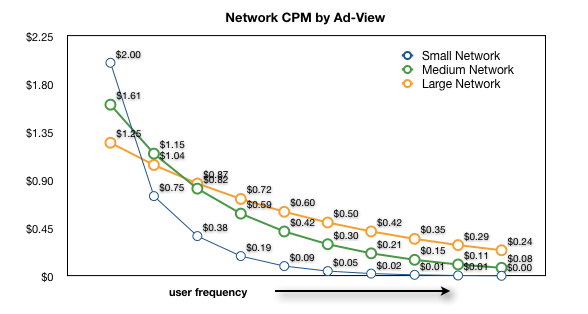

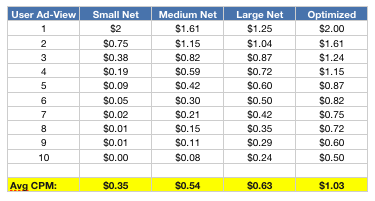

Hence the effective CPM that you receive per user from a network declines as that network continues to see him over and over again. The larger the network the slower the decline, but each will look similar — here’s a rather rough sketch of what various network payout look like (again, numbers are hypothetical, but shape of graph will generally be correct).

Obviously daisy-chaining will not work in this situation as both the medium and large networks have paying ads for each individual ad-view. In the hypothetical example above, you would want an individual user to see the following sequence of ads to maximize revenue:

- Small

- Medium

- Large

- Medium

- Large

- Large

- Medium

- Small

Comparing the effective CPM of each network individually versus optimized together:

What you see is that you can vastly increase your CPMs by distributing your networks. Now — although these are fictional numbers — the concepts are real and they work. So how do you do it? Rather simple!

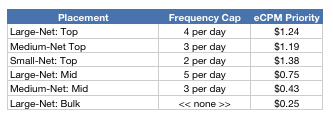

It’s impossible to allocate impressions on a per view basis as I did above so we must rely on a little bit of approximation. The way to do this is to setup multiple placements or zones with your ad-network and then to frequency cap them individually within your own adserver. The above could look something like this:

The key here is not to over-complicate. Sure, a Myspace, Facebook or Bebo may create hundreds of different placements each with different caps and priorities, but there are two reasons you shouldn’t

- It’s incredibly resource intensive to manage

- You don’t have enough inventory

Each placement needs to run a minimum amount of volume otherwise pulling out the effective CPM will be nearly impossible. A lot of pricing is based around user response to ads — eg CPC or CPA based pricing. Since clicks and conversions are rare events you need to have enough volume in each placement to get a predictable effective CPM. On CPC networks you can probably get away with a couple thousand impressions per placement per day but on CPA you’ll want to go closer to ten to twenty thousand.

There is some art here as you will have to update both the frequency caps and the pricing on your placements regularly. The first couple times chances are you’ll see your network cpms fluctuate as you play with the caps & inventory allocations but as you get a hang of it you should gain some serious lift.

Enough for today — next, how to effectively target network placements to maximize revenue.

Exchange v. Network, Part I: What’s the difference?

August 16th, 2007

The “Exchange” Buzz!!

Back in May I started a three part series on “The Ad Exchange Model” where I focused primarily on the technical benefits that exchanges bring to the online advertising industry. Since then exchanges have received quite a bit of press with all the recent acquisitions and the word exchange has reached buzz-word status, without much understanding of what it actually means. Perhaps most confusing is that many don’t seem to be able to differentiate between an Exchange and an Ad-Network. For example, compare these two quotes from iMedia and Ad.com, can you tell what the difference is?

“An ad exchange is a company that brokers online advertising by bringing publishers and advertisers together on a website where they can participate in auctions for ad space.” iMedia Connections — Ad Exchanges At a Glance

“Websites have ad space. Advertisers have ads. We’re the middle man – using our phenomenal technology to match ads to space.” Advertising.com Homepage

The ‘Nasdaq’ Analogy

One of the most common explanations I have heard goes something like this — “An ad-exchange functions just like the Nasdaq.” (this is in no way a jab at ContextWeb’s Adsdaq, this analogy is regularly used on all ad-exchanges). You like the Nasdaq right? Good, the Nasdaq is efficient has some fancy electronic trading and does lots of good things, which is why you should buy this ad-exchange. Oh, well of course! Ad exchanges bring efficiency just like the Nasdaq does, that makes absolute perfect sense! Try explaining an ad-exchange like this, it’s actually quite amusing. Generally what happens is the other person’s eyes glaze over slightly and he starts nodding as if everything has been made extremely clear even though he still has no clue what the ad-exchange actually does. You see, the Nasdaq analogy really doesn’t make sense but nobody wants to sound stupid and say “I don’t get it”, so they let it slide and remain confused.

So why doesn’t it make sense? Well, we could argue semantics of stock markets versus commodity and future exchanges — but who cares. The real problem is that the Nasdaq analogy works just as well for Advertising.com as it does for Right Media, adECN or AdsDaq. The Nasdaq is a mechanism which enables people to buy and sell stocks. Ad-networks are mechanisms by which people buy and sell ad-inventory. If this is surprising, it shouldn’t be — an ad-network is a mini-marketplace, very similar to an exchange or stock-market. The whole reason we have them to begin with is to enable thousands of sites to work with thousands of buyers. Can you imagine Netflix writing individual checks to the thousands of different sites where their ads are displayed?

So what’s the difference

Even though an ad-network may perform many of the same functions as an exchange there is a subtle difference. The network operates and controls all aspects of the mini-marketplace whereas the exchange is an “agnostic” platform that many buyers and sellers use to run their own businesses. In most ad-network limits each transaction (or ad-impression) to three parties: a buyer, the network and a seller. The exceptions to this would be networks such as Tacoda where a fourth data-provider might receive a cut of the transaction based on information about the user that the network provided. Of course in reality online advertising is far more complex than that and a single online ad impression can involve far more parties.

That’s where the exchange model shines — instead of one party “operating” the exchange on behalf of a number of buyers and sellers, the exchange provides a single technology platform upon which many companies — advertisers, publishers and networks — can buy and sell ads. Each impression can have anywhere from zero to many middlemen.

Who cares?

First off, the exchange is many companies versus one in the case of the ad-network. The platform is an ecosystem that supports a large variety of business models which results in more innovation and competition. Then there are certain basic technical benefits from having multiple participants in a transaction use the same platform, something that isn’t possible with an ad-network. For example, a proper exchange removes the operational barriers that have limited access to inventory in the past are eliminated in an ad-exchange. This enhanced the liquidity of the marketplace, which results in higher and more stable rates for publishers. I’ve covered most of these benefits in detail in my ad-exchange series.

Of course some of the above is still somewhat theoretical as we are just now starting to see the exchange model mature. As the model grows, most standalone networks will find life difficult without some level of integration with one or more of the coming exchanges.

In Parts II & III of this series I’ll talk about some tactical steps Publishers and Advertisers can take to leverage exchanges as either sources of inventory or pools of advertisers to maximize ROI and revenue and perhaps some bits on how Networks can different themselves in the coming landscape.